Ear Symptoms

It is healthy and normal for ears to produce wax. Wax production is part of the way that ears keep themselves clean and reduce the risk of infection. However a more profuse and liquid discharge from the ears is usually a sign of infection either in ear canal (the outer ear) or through a perforation of the ear drum (middle ear). Such discharge requires specialist evaluation and treatment if it is persistent or keeps recurring.

We all experience earache from time to time but persistent pain, whether superfial or deep in the ear requires assessment to find the cause and instigate treatment. The cause of the pain may be due to a problem with the outer or middle ear, most commonly infection. However the ear shares a complex nerve supply with other structures in the head and neck and therefore conditions such as throat, sinus and dental infections as well as arthritis of the neck and jaw-joinst can all cause pain in the ear.

Hearing loss may affect people of all ages from infants (born with hearing loss), young children, where glue ear is a common cause, through to older people with age related loss.

Broadly speaking we divide hearing loss into 2 groups:

Conductive loss where there is impairment of sound transmission due to disorders of the ear canal, ear drum or tiny bones in the middle ear.

Such hearing loss may be amenable to surgical intervention and improvement in the hearing.

Sensorineural loss where the problem lies within the inner ear (the cochlea, which converts mechanical sound waves into electrical nerve impulses)

Mild and moderate sensorineural hearing loss is best managed with well-fitted hearing aids although in certain situations, middle ear implants will confer greater benefit.

The commonest cause of sensorineural hearing loss is the decline with increasing age. This is particularly affects high frequency sounds which makes understanding speech in background noise particularly difficult. The provision of appropriate hearing aids helps in most instances.

Conversely, hearing loss from birth (congenital hearing loss) should be identified in all UK new-borns as the hearing is tested within a few weeks of birth. Congenital hearing loss is therefore picked up at the earliest opportunity and hearing aids can be fitted where appropriate. When the loss is severe or profound cochlear implantation can be utilised.

Specific Conditions

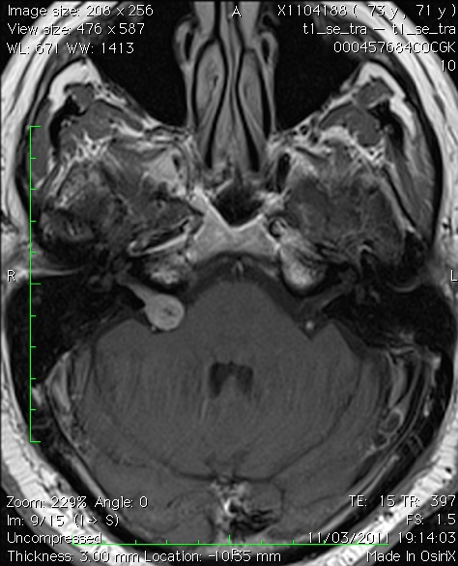

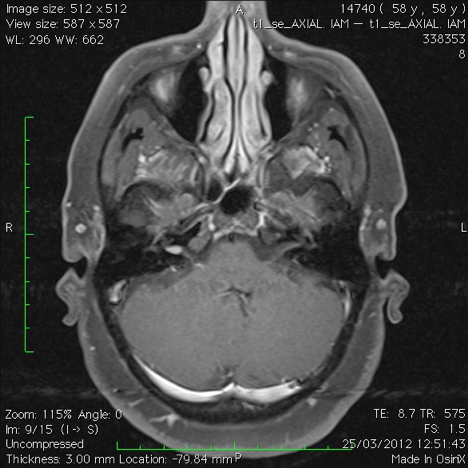

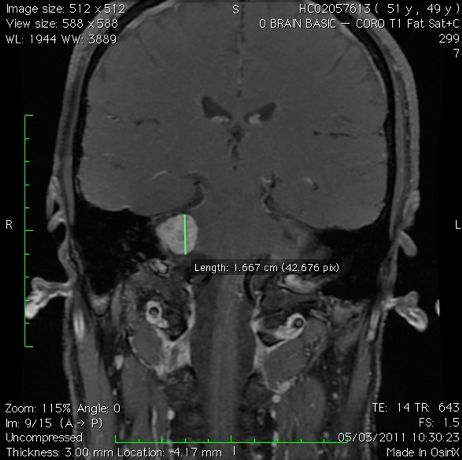

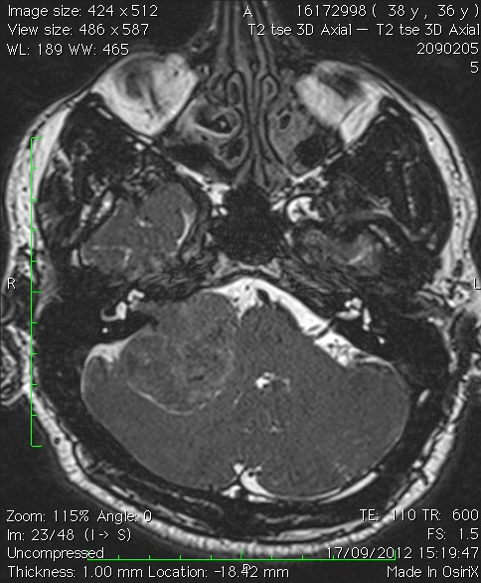

Vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma)

These are benign tumours that arise from balance nerves as they travel from the inner ear towards the brain. They affect 1 in 50,000 of the adult population and the majority are slow growing (average growth rate 2mm per year. The tumour usuallly causes gradual progressive hearing loss in the affected ear sometimes over many years. The hearing loss can however occur suddenly in around 1 in 20 patients. Other symptoms include tinnitus, balance problems and facial numbness.

Over the last 15 years it is clear that as many of 65% of such tumours develop and then stop growing, particularly smaller tumours in older individuals. On this basis there are potentially 3 management options for patients with a vestibular schwannoma namely, regular monitoring with serial MRI scans to see if the tumour is actually growing before intervention, specialised stereotactic radiotherapy ( fractioned/gamma knife/cyberkinife) to stop tumour growth and microsurgical removal of the tumour for larger tumours or if the patient prefers this option. Based on his extensive experience in this field, Prof Saeed will discuss these options in detail, reaching a decision with you based on your individual situation. This will include discussing your case with his multidisciplinary team at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery.

MRI of a small intracanalicular vestibular schwannoma

MRI of a small vestibular schwannoma

MRI of a medium-sized vestibular schwannoma

MRI of a large vestibular schwannoma

Serial imaging

In line with the policy devised by Prof Saeed and colleagues when he was President of the British Skull Base Society, new patients presenting with a small or medium sized tumour will undergo a repeat MRI 6 months after their original scan to establish whether the tumour is growing. If there is growth then one of the two otions below are considered. If there is no growth then the tumour can be monitored with the next MRI a year later and so on. In our experience the majoriy of tumours that are growing do you this on MRI with 5 years of the diagnosis.

Stereotactic radiotherapy treatment

This may take the form of a single targeted intense dose of radiotherapy (gamma knife) or smaller multiple dose (cyberknife and fractionated). Whichever one is used the aim is to stop the tumour from growing rather than getting rid of it (unlike radiotherapy for cancer). The advantages of radiotherapy are that you avoid major surgery and there is around a 90% chance of achieving this whether you have the single shot (gamma knife) or multiple shots (fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy). You would then require subsequent imaging for the foreseeable future to check that the tumour has stopped growing and indeed does not start growing once again. If the tumour does grow and subsequent surgery is required then it is our experience that this can sometimes be more difficult because of scarring from the previous radiotherapy. The radiotherapy carries a very small risk to adjacent nerves including your facial nerve and a rare risk of the development of a malignant tumour many years down the line though this is exceedingly uncommon.

Microsurgical removal of the tumour

Prof Saeed and his Neurosurgical team undertake this in larger tumours or smaller tumours that continue to grow after radiotherapy of on occasion as an attempt to preserve hearing with small tumours if the patient request this.

The aim of the surgery is to remove the tumour completely without causing any additional neurological harm. In our hands the operation will take about 4 and 8 hours depending on the size of the tumour and involve a hospital stay of usually between 6 – 10 days. The main period of convalescence is the first month after surgery with a return to work after 2 months to 4 months depending on the extent of surgery and the patient’s recovery and occupation. If total tumour removal is achieved then a MRI scan is done 9 to 12 months later and if the patient is tumour free then that would be the end of the matter if all is well. If we have purposely left a small amount of tumour to avoid injury to adjacent nerves and the brain (often the case now with large tumours) then the remaining tumour is monitored with serial MRI over many years and treated with stereotactic radiotherapy if there is evidence of growth on the scans.

With regards to risks of surgery the chances of catastrophic event such as loss of life or stroke is less than 1%. The chance of serious complication such as infection (meningitis) or clots in the legs or lungs is around 1%. The risk to the face sensation nerve and swallowing and voice nerves depends on the size of the tumour but is around 1%.

If the operation is via the translabyrinthine approach this results in complete hearing loss on that side but the advantage is that it gives a direct route to the tumour and the facial nerve.

The retrosigmoid approach may preserve some hearing but often with large tumours this is not the case. Prof Saeed and his team rarely do the middle fossa approach for very small tumours as we find that many such small tumours do not actually grow and the decline in hearing can be over many years.

The risk to the facial nerve depends again on the size of the tumour and in our hands there is around a 80 to 95% chance we can preserve norma l or near normal facial function. To achieve this we will leave tiny fragments of tumour on the nerve if there is a risk that the nerve would be further damaged by removing these. Such fragments often disappear on subsequent scanning or remain stable.

Finally at the end of the operation we may take some fat from your abdominal wall in order to fill the cavity created behind the ear under the scalp. Despite this there is around a 2% chance that the fluid that bathes the brain can leak either through the wound or through what is left of the ear bone into the back of the nose. This is a nuisance and occasionally required a return to theatre.

Glomus tumour (paraganglioma)

Glomus tumours (also known as paragangliomas) are benign, very vascular, slow-growing locally destructive tumours that arise in different areas in the head and neck including the middle ear and the jugular bulb area. They usually present with pulsating tinnitus, hearing loss and ear blockage. They can also present with voice and swallowing problems. The treatment options include regular monitoring with scans, radiotherapy or surgery. If your tumour is small or medium sized then surgical removal is the preferred option as there is a good chance of complete removal, often with preservation of useful hearing. If the tumour is very extensive then treatment may be a combination of surgery to remove around 75% of the tumour followed by specialised radiotherapy to stop the remaining tumour from growing. This reduces the risk of surgery causing permanent harm to the nerve that moves the face as well as those of voice and swallowing.

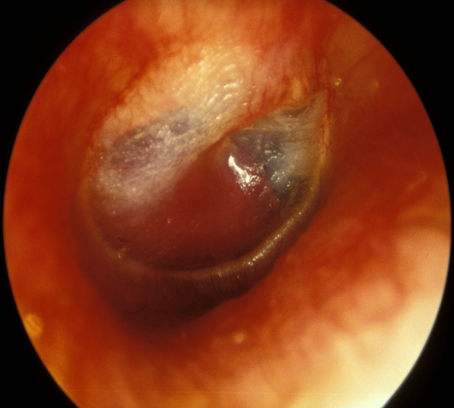

The picture below shows a typical bright red glomus tumour visible behind the ear drum.

Cholesteatoma

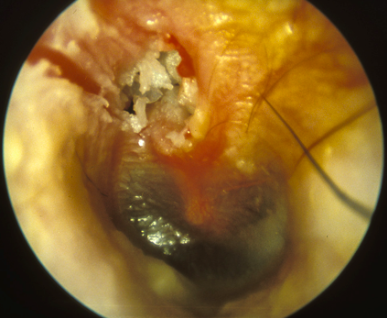

In this condition skin which lines the ear canal and ear drum can grow into the space behind the drum, middle ear. This collection of skin can cause recurring infections often with a smelly discharge. Whislt cholesteatoma is not a tumour it tends to damage surrounding bone and structures in the ear leading to hearing loss and balance problems. Less commonly it can damage the nerve that runs through the ear bone and moves the face muscles leading to facial palsy. Rarely the disease can spread beyond the confines of the ear bone leading to infection or abscess in the head cavity itself. For these reasons surgery is almost always necessary to remove the cholesteatoma and try and improve any hearing loss, thereby minimising the risks of the disease itself. The extent of the surgery will depend on the extent of the cholesteatoma but usually takes between 2 and 4 hours with a hospital stay of 1 night and a period of convalescence for 2 weeks.

The picture below shows an ear drum with a perforation and cholesteatoma at the top.

Otosclerosis

This is a condition whereby the third of the 3 bones of hearing in the middle ear, the stapes, can become fixed due to abnormal new bone formation on it. This impedes the transmission of sound to the inner ear resulting in a hearing loss. The disease tends to start in young adulthood and can affect both ears. Hearing aids can be very helpful. However otosclerosis is one of the few ear conditions where surgery can produce dramatic improvements in hearing in around 90% of patients under Prof Saeed’s care. However the surgery (stapedotomy) carries an uncommon but serious risk of substantial permanent hearing loss (around 0.5%) and therefore Prof Saeed always considers the decion to proceed wth surgery with his patients very carefully.

The picture below shows various stages of the stapedotomy operation for otosclerosis.

Facial nerve tumours

These are rare tumours and therefore patients with this type of problem are referred to only a handful of surgeons in the UK including Professor Saeed. Many such tumours are managed by monitoring with scans sometimes over many years as the tumour may not grow and the patient’s facial movement remains normal. However if the tumour does grow and the facial movement starts to reduce then Professor Saeed can remove the tumour and graft the facial nerve to restore some facial movement.

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome (SSCDS)

Awareness of this uncommon but potentially debilitating condition has increased over the last 2 decades – in the UK a small number of neuro-otologists including Professor Saeed manage such patients. The symptoms broadly fall into two areas – abnormal hearing and disturbance of balance. The former include hearing one’s voice abnormally loudly or as a reverberation in the affected ear (autophony) and hearing body noises (eyeballs moving, joints creaking, bowel sounds, footfall) in the affected ear. It is these symptoms that can be particularly intrusive. In addition external noises can sound disablingly loud (hyperacusis) or can give rise to imbalance or dizziness (Tullio phenomenon). Individuals with SSCDS do not usually have spontaneous episodes of dizziness but have varying degrees of impaired balance or dizziness triggered by unfavourable external environments.

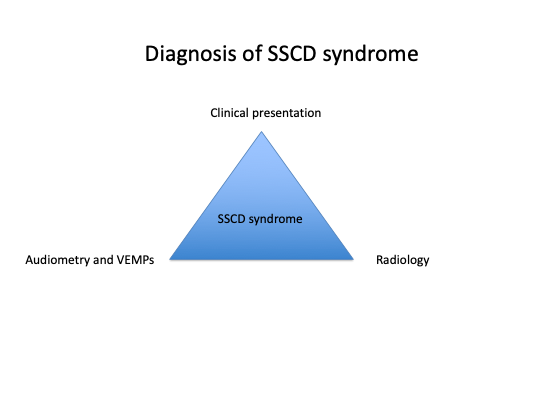

The diagnosis is based on 3 components coming together – what Prof Saeed calls the diagnostic triangle as shown below.

The clinical picture, consistent audiovestibular tests (especially the VEMPs) and dehiscence of the superior canal on CT scanning are key to making the correct diagnosis. The presence or absence of a dehiscence can sometimes be mis-leading on conventional CT scans and Prof Saeed prefers the detail seen on cone-beam CT scanning to clearly show the hole in the canal (or indeed thinning of the bone over the canal). The pictue below shows this. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should exclude other causes of the patients symptoms

Once the diagnosis is made the management depends on how much of an impact the symptoms are having on the patient’s day to day life, family, work and general well-being. Prof Saeed has found that around three-quarters of patients referred to him have symptoms that are debilitating to the point that the patient requests surgical intervention.

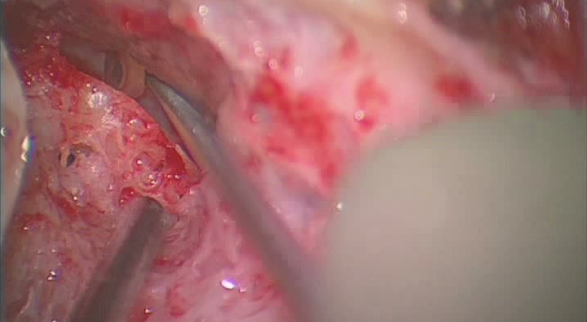

Superior canal dehiscence surgery includes resurfacing of the defect in the canal, plugging of the canal or a combination of the two. The canal can be reached via the middle fossa (MF) approach or through the mastoid bone behind the ear (transmastoid, TM approach). The approach may be dictated by the patient’s anatomy but Prof Saeed has found that the majority can be undertaken using either approach and he has considerable experience of both approaches for a variety of conditions, not just SSCDS. As the TM approach does not involve opening the head cavity itself with the associated risks his preference is the TM approach. His initial 20 such TM surgical cases involved just resurfacing the dehiscence with the patients own bone but only had a three-quarters success rate in terms of significantly reducing or abolishing the troublesome symptoms (see publications). For his subsequent 40+ surgical cases Prof Saeed has also plugged the canal up and downstream to the dehiscence increasing the success rate to 9 out of 10. This still means that despite technically similar surgery in each patient, there is a 10% risk of less than satisfactory resolution of the troublesome symptoms. The surgery also carries around a 5% risk if significant permanent hearing loss (research paper being prepared for publication).

The surgery takes Prof Saeed around 2 hours and involves a typical hospital stay of 1 or 2 nights. However a small number of patients are very dizzy after the operation and require a longer hospital stay. It is common for the operated ear to feel blocked with muffled hearing for 2 to 3 months and sometimes longer. The balance recovery after the surgery seems to be very variable with some patients substantially better after 2 weeks and others taking many months.

For these reasons, the decision to proceed to surgery is carefully considered by Prof Saeed and his patients and balanced against the impact of the condition on the patient’s daily life.

The picture below shows a left transmastoid surgical approach with the dehiscence of the canal being visualised indirectly with a tiny mirror prior to resurfacing and plugging.

Meniere’s Disease

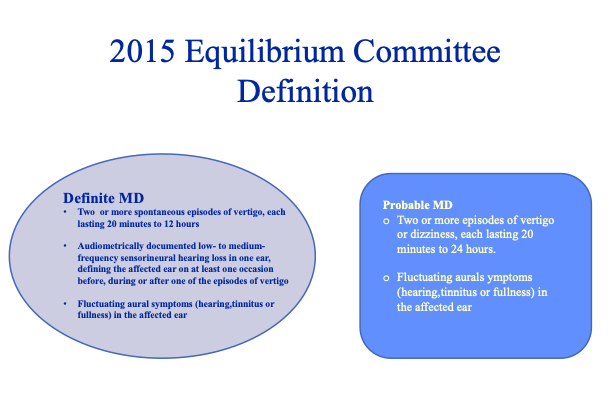

Meniere’s disease is a relatively uncommon inner ear disorder and is diagnosed if the 4 classic symptoms are present: Variably disabling attacks of dizziness (vertigo), hearing loss in the affected ear, tinnitus and a full blocked feeling in the ear. The definition of Meniere’s diseaseis as below:

Because of his expertise in this area, Professor Saeed has accrued a substantial experience in this disorder over the last 25 years and is able to offer the full range of treatments to help his patients. Around 80% of patients respond to medical treatment with a combination of various drugs. For those that do not respond to such conservative measures the next step is to use corticosteroid injections through the ear drum under local anaesthetic to calm the active inner ear down. If this fails (usually a course of up to 3 injections) then surgery can be considered. This can be either be hearing preserving surgery when the hearing is still useful such as endymphatic sac decompression or vestibular neurectomy or hearing destructive surgery when the disease itself has caused severe hearing loss (labyrinthectomy). Professor Saeed discusses all these options in terms of benefit and risks so as to individualise the management of this disabling condition.

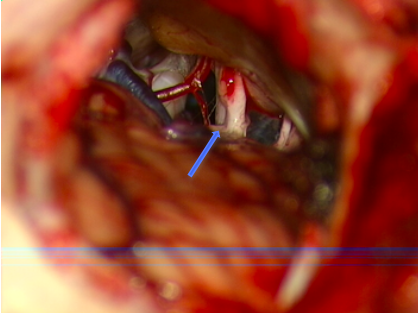

The picture below shows Prof Saeed undertaking a vestibular neurectomy operation with the arrow pointing to where the nerve has been cut.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

BPPV is a common condition whereby short lived acute episodes of dizziness are elicited by specific head movements, classically turning over on bed. This can be easily diagnosed using Hallpike’s test in the clinic setting and then effectively treated by specific movements of the head, the Epley or Semont manoeuvre.

Hearing loss requiring auditory implantation (cochlear implants, middle ear implants, bone conduction implants and brainstem implants)

Until the late 1980s, adults who became severely or profoundly deaf in both ears or children born with profound hearing loss had little in the way of medical technology to help them as the hearing loss was beyond even the most powerful hearing aids.

Cochlear implants have revolutionised the management of severe-profoud hearing loss: adults return to the hearing world again and children often develop speech and language. These implants are inserted into the non-functioning cochlea nd electrically stimulate the hearing nerve directly. Whilst cochlear implants do not restore natural hearing in the true sense their impact has been huge at a global level. Professor Saeed was fortunate to be involved in this field from the outset and has extensive experience in this area. He and his audilogical team undertake a formal and detailed assessment of potential candidates (adults and children) and then advise if a cochlear implant will be suitable. The surgery is relatively straightforward in most instances but the real hard work starts afterwards with the patient having to learn to use the device to its full effect with support from his expert team.

In more recent years Professor Saeed has successfully implanted individuals with single-sided profound hearing loss and useful hearing in the opposite ear to good effect.

For those individuals who have moderate natural hearing in one or both ears but cannot use conventional hearing aids to good effect, middle ear implants or bone conduction implants may be considered. Prof Saeed can discuss this in detail based on his experience with such implants.

Finally, in the rare instances where a child is born with profound hearing loss in both ears and a cochlear implant cannot be used (usually due to absent hearing nerves), an auditory braintem implant may be considered. This is a huge decision for the family and involves a detailed assessment and discussion with shared decision-making.

In summary, the majority of hearing losses can be helped with conventional hearing aids or a range of auditory implants depending on individual circumstances and the degree of hearing loss in both ears. Professor Saeed is the only surgeon in the UK that has experience of all types of auditory implants and he and his team can advise accordingly. The pictures below show the various types of auditory implants he uses:

Internal & external components of a cochlear implant system

External components of a cochlear implant system

Internal and external components of the Bonebridge implant

Internal components of a brainstem implant